Thursday, March 20, 2025 — Arizona state lawmakers clash on rural groundwater rules—debating economic impacts, local control, and sustainability amid the state’s deepening water crisis.

Key Points:

- GOP Critique: Arizona House Republicans claim a new 87-page rural groundwater management proposal (SB 1425)

would impose drastic restrictions – including “mandatory groundwater cuts of up to 40 percent over 40 years” – and “devastate rural economies,” calling it an anti-growth overreach.

would impose drastic restrictions – including “mandatory groundwater cuts of up to 40 percent over 40 years” – and “devastate rural economies,” calling it an anti-growth overreach. - Democrats’ Stance: Democratic leaders, backed by Governor Katie Hobbs, argue the Rural Groundwater Management Area plan is a long-overdue step to protect dwindling rural aquifers

with local oversight after decades of inaction. “Our world is much different today … and our laws need to reflect the changing environment and needs of rural communities,” Hobbs said, urging bipartisan support.

with local oversight after decades of inaction. “Our world is much different today … and our laws need to reflect the changing environment and needs of rural communities,” Hobbs said, urging bipartisan support. - Water at Stake: The debate highlights Arizona’s groundwater challenges – most rural areas lack regulation, leading to declining wells amid a historic drought. Both parties agree on safeguarding water for the future, but disagree sharply on approach, balancing conservation needs against local control and agricultural livelihoods.

Background: A Growing Groundwater Problem.

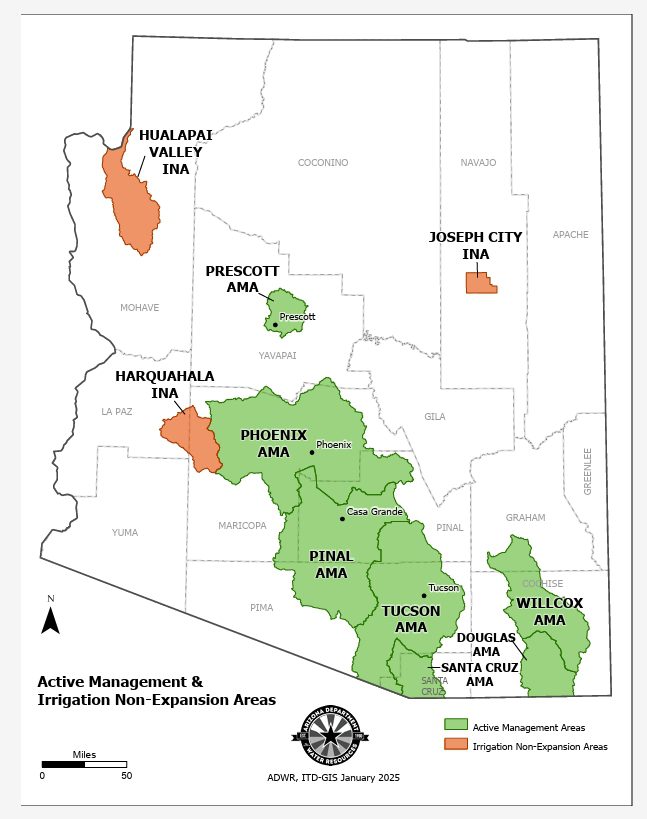

Arizona has long grappled with how to manage its groundwater, especially in rural areas. In 1980, the state passed the Groundwater Management Act, which set up Active Management Areas (AMAs) to regulate pumping in urban regions like Phoenix and Tucson. However, most rural parts of Arizona were left with few restrictions on groundwater use, relying on wells tapping ancient aquifers. Decades of over-extraction and prolonged drought have taken a toll in some areas of the state: water tables have dropped and “many wells run the risk of drying up ” in some communities. This puts farms, ranches, and homeowners in these areas at risk as aquifers are steadily depleted.

” in some communities. This puts farms, ranches, and homeowners in these areas at risk as aquifers are steadily depleted.

One high-profile example is the Willcox Basin in southeastern Arizona, a farming region where heavy irrigation has led to significant declines in groundwater levels. In 2022, local voters rejected a proposal to designate Willcox as an Active Management Area (which would mandate conservation), reflecting wariness toward government regulation. State officials, citing alarming data on declining aquifers, later moved to impose an AMA there in late 2024 – a controversial decision that rural advocates saw as an override of local wishes. Similar struggles are playing out in other basins like those near Kingman and in La Paz County, where large-scale farming (including foreign-owned farms) has pumped groundwater aggressively, causing concern among local residents and officials about wells running dry.

Against this backdrop of wells drying and land subsiding, policymakers on both sides of the aisle agree that Arizona’s rural water usage is unsustainable without new measures. The question is how to craft solutions that protect water supplies for future generations while preserving rural economies that depend on agriculture and development.

Republicans Warn of Economic Impacts.

This week, Arizona House Republicans, led by Representative Gail Griffin (R-Hereford), made their stance clear in a strongly worded press release. Griffin, who chairs the House Natural Resources, Energy & Water Committee, slammed the Democrats’ new groundwater plan as an extreme approach that would hurt rural communities. “Many areas across rural Arizona are facing challenges with groundwater resources. To address these challenges, Republicans in the State Legislature have been working on solutions to secure Arizona’s long-term water future,” Griffin said in the statement, emphasizing that the GOP has been active on water issues. She noted that since 2023, Republican lawmakers have convened over a hundred stakeholder meetings across Arizona and introduced numerous bills aimed at bolstering water supplies “without compromising our principles.”

as an extreme approach that would hurt rural communities. “Many areas across rural Arizona are facing challenges with groundwater resources. To address these challenges, Republicans in the State Legislature have been working on solutions to secure Arizona’s long-term water future,” Griffin said in the statement, emphasizing that the GOP has been active on water issues. She noted that since 2023, Republican lawmakers have convened over a hundred stakeholder meetings across Arizona and introduced numerous bills aimed at bolstering water supplies “without compromising our principles.”

Griffin recounted several Republican-led proposals from recent sessions intended to tackle groundwater decline through local-friendly measures. Those initiatives included establishing new Irrigation Non-expansion Areas (which restrict new farmland in heavily pumped basins) – for example, designating Willcox as an INA instead of an AMA – and bills to promote stormwater recharge projects in vulnerable basins and grant rural well owners more property rights to groundwater. While many of these GOP proposals did not advance last year amid political gridlock, they illustrate Republicans’ preference for voluntary conservation, incentives, and incremental regulation rather than sweeping mandates. “House and Senate Republicans have introduced over 20 measures on rural groundwater [this year],” Griffin’s release noted, aimed at conserving water, increasing recharge, and improving data on aquifer conditions.

from recent sessions intended to tackle groundwater decline through local-friendly measures. Those initiatives included establishing new Irrigation Non-expansion Areas (which restrict new farmland in heavily pumped basins) – for example, designating Willcox as an INA instead of an AMA – and bills to promote stormwater recharge projects in vulnerable basins and grant rural well owners more property rights to groundwater. While many of these GOP proposals did not advance last year amid political gridlock, they illustrate Republicans’ preference for voluntary conservation, incentives, and incremental regulation rather than sweeping mandates. “House and Senate Republicans have introduced over 20 measures on rural groundwater [this year],” Griffin’s release noted, aimed at conserving water, increasing recharge, and improving data on aquifer conditions.

By contrast, Republicans argue, the Democrats’ new plan takes a far more heavy-handed path. Griffin’s statement accuses the Democratic proposal of reviving ideas that GOP negotiators had previously flagged as unacceptable. “Democrats halted participation [in talks] in June 2024 and, six months later, released an 87-page proposal without advance notice,” she said , expressing frustration at how the plan was unveiled. According to Griffin, the Democratic plan echoes an “anti-growth agenda” pushed by “radical environmentalists” that would impose California-style regulations on rural Arizona.

, expressing frustration at how the plan was unveiled. According to Griffin, the Democratic plan echoes an “anti-growth agenda” pushed by “radical environmentalists” that would impose California-style regulations on rural Arizona.

In particular, the press release lists a series of stringent provisions in the 87-page bill that Republicans find objectionable. These include:

in the 87-page bill that Republicans find objectionable. These include:

- Steep mandatory cuts: New rural management areas would require “mandatory groundwater cuts of up to 40 percent over 40 years” – effectively forcing users to gradually pump much less water. Griffin warns that “for farmers, a 40 percent groundwater cut means a 40 percent cut in livelihoods. For local governments, it’s a 40 percent loss in revenue. This would devastate rural economies.”

- New regulatory councils: The plan would create regional groundwater councils appointed largely by the governor. Republicans argue these “unelected, Governor-appointed councils” wouldn’t themselves face pumping limits but could “impose new regulations on others, targeting individual water users and shutting down local industries.” GOP lawmakers see this as undermining local control, putting decisions in the hands of Phoenix bureaucrats.

- Metering and fees: Farmers and well owners would be subject to mandatory metering and reporting of water use, and potentially new withdrawal fees – essentially a tax on groundwater pumping. Those fees, set by state agencies, could increase costs for rural water users.

- Limits on new wells and development: In some cases, drilling new or replacement wells could require state approval, and establishing a new regulated area would not require local voter consent under the proposal. Republicans worry this opens a “backdoor” for state government to override county authorities on water and even housing developments in the name of conservation.

Griffin and her GOP colleagues contend such measures go too far. They point out that urban AMAs, which have regulated Phoenix, Tucson and other cities since 1980, never imposed cuts as severe as 40%, and they question why rural communities should bear that burden. “If Democrats and radical environmental groups think a 40 percent cut is necessary to save Arizona’s groundwater resources, then why don’t they propose 40 percent cuts in the Phoenix or Tucson [AMAs], where over 80 percent of the state’s population resides?” Griffin wrote, challenging the fairness of the plan . The implication is that the proposal could stall growth and agriculture in rural Arizona, while cities would face no such new restrictions.

. The implication is that the proposal could stall growth and agriculture in rural Arizona, while cities would face no such new restrictions.

At the same time, Republican leaders insist they share the goal of protecting water – just through different means. Griffin’s statement highlights that agriculture is vital to Arizona’s economy (accounting for $31 billion annually and a large share of the nation’s winter produce), and it credits farmers for improving water efficiency with new technology. Rather than strict government mandates, Republicans favor incentives for innovation and voluntary conservation measures. “Does more work need to be done? Yes,” Griffin conceded, “but [we] believe in taking a different approach than the top-down method currently being pushed. Rural Arizonans deserve better. Together, we can find a ‘win-win’ solution.”

to Arizona’s economy (accounting for $31 billion annually and a large share of the nation’s winter produce), and it credits farmers for improving water efficiency with new technology. Rather than strict government mandates, Republicans favor incentives for innovation and voluntary conservation measures. “Does more work need to be done? Yes,” Griffin conceded, “but [we] believe in taking a different approach than the top-down method currently being pushed. Rural Arizonans deserve better. Together, we can find a ‘win-win’ solution.”

The GOP release ends with a call to put politics aside and collaborate on “real solutions for rural Arizona” that sustain both water and the economy.

Democrats Push for Local Water Protections.

Democratic leaders and water advocates have a very different view of the situation. They argue that doing nothing is not an option as groundwater levels plummet in parts of rural Arizona. Governor Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, has made rural water reform a priority of her administration. In late January, flanked by bipartisan local officials from affected communities, Hobbs unveiled the legislative proposal now under debate. “Politicians have not taken serious action in rural Arizona since the Groundwater Management Act passed in 1980,” Hobbs said at the rollout

as groundwater levels plummet in parts of rural Arizona. Governor Katie Hobbs, a Democrat, has made rural water reform a priority of her administration. In late January, flanked by bipartisan local officials from affected communities, Hobbs unveiled the legislative proposal now under debate. “Politicians have not taken serious action in rural Arizona since the Groundwater Management Act passed in 1980,” Hobbs said at the rollout , noting the decades-long regulatory gap. “Our world is much different today than it was then, and our laws need to reflect the changing environment and needs of rural communities.” In other words, proponents of the legislation say that with climate change and continued growth, rural water use can’t remain unchecked without courting a crisis.

, noting the decades-long regulatory gap. “Our world is much different today than it was then, and our laws need to reflect the changing environment and needs of rural communities.” In other words, proponents of the legislation say that with climate change and continued growth, rural water use can’t remain unchecked without courting a crisis.

The Democratic plan, formally introduced as the Rural Groundwater Management Act of 2025 , seeks to empower local regions to manage their water before it’s too late. The bill (87 pages long, as Republicans noted) would establish Rural Groundwater Management Areas (RGMAs) in a handful of especially stressed basins across Arizona. Initially, four areas are targeted – the Gila Bend Basin, Hualapai Valley Basin (near Kingman), Ranegras Plain Basin, and the San Simon Basin

, seeks to empower local regions to manage their water before it’s too late. The bill (87 pages long, as Republicans noted) would establish Rural Groundwater Management Areas (RGMAs) in a handful of especially stressed basins across Arizona. Initially, four areas are targeted – the Gila Bend Basin, Hualapai Valley Basin (near Kingman), Ranegras Plain Basin, and the San Simon Basin – all places where groundwater levels have been dropping rapidly, and current law provides few tools to intervene. In addition, the Willcox Basin’s new Active Management Area (imposed in 2024) would be converted to this rural model, to ensure a consistent approach statewide.

– all places where groundwater levels have been dropping rapidly, and current law provides few tools to intervene. In addition, the Willcox Basin’s new Active Management Area (imposed in 2024) would be converted to this rural model, to ensure a consistent approach statewide.

Within each RGMA, there would be a local five-member council to oversee groundwater use. Supporters emphasize that a majority of each council must be local residents of the area, and the council is tasked with tailoring conservation goals that make sense for that region. “The proposed councils put decision-making closer to the community,” Democrats argue, pushing back against the idea of a Phoenix takeover. While the governor would appoint council members (from lists recommended by legislative leaders of both parties), the intent is to include local farmers, ranchers, and officials who understand the area’s needs. These councils would have the authority to set conservation programs and limits on large water users and adjust those rules over time based on progress (every 10 years, per the bill). The aim is to slow down the aquifer decline to sustainable levels – for instance, by moving toward “safe yield” (balancing recharge and withdrawals) or other goals chosen from a provided menu of options.

on large water users and adjust those rules over time based on progress (every 10 years, per the bill). The aim is to slow down the aquifer decline to sustainable levels – for instance, by moving toward “safe yield” (balancing recharge and withdrawals) or other goals chosen from a provided menu of options.

Democratic lawmakers contend that this approach actually preserves local control more than alternative solutions would. “This comprehensive plan was born out of the consensus of the diverse business and municipal interests represented on the governor’s water policy council, followed by months of stakeholder meetings, constituent engagement and honest conversations with the agricultural community,” said Sen. Priya Sundareshan (D-Tucson), a key sponsor, when introducing the bill. In her view, the proposal is not a surprise ambush but rather the product of lengthy negotiations among water experts, city and county leaders, farmers, and ranchers. Democrats note that a wide range of stakeholders – from the Arizona Farm Bureau to environmental groups – have publicly acknowledged the need for rural groundwater management, even if they disagree on specifics. This broad concern helped build what Hobbs calls a “good place” of common ground compared to prior years.

(D-Tucson), a key sponsor, when introducing the bill. In her view, the proposal is not a surprise ambush but rather the product of lengthy negotiations among water experts, city and county leaders, farmers, and ranchers. Democrats note that a wide range of stakeholders – from the Arizona Farm Bureau to environmental groups – have publicly acknowledged the need for rural groundwater management, even if they disagree on specifics. This broad concern helped build what Hobbs calls a “good place” of common ground compared to prior years.

Environmental advocates generally back the Democratic plan, seeing it as an overdue first step. “This Legislature, by and large, has ignored [rural residents], and they now have an opportunity to do something with this bill,” said Sandy Bahr, director of the Sierra Club’s Arizona chapter . Her group would actually like the law to go further – “we would like it to include more mandatory requirements,” Bahr admits – but she also calls it “a good start” that at least establishes protections in areas that desperately need it. Other conservation organizations, such as the Environmental Defense Fund, have similarly advocated for stronger groundwater rules in rural Arizona in recent years, warning that failing to act will jeopardize the state’s water future.

. Her group would actually like the law to go further – “we would like it to include more mandatory requirements,” Bahr admits – but she also calls it “a good start” that at least establishes protections in areas that desperately need it. Other conservation organizations, such as the Environmental Defense Fund, have similarly advocated for stronger groundwater rules in rural Arizona in recent years, warning that failing to act will jeopardize the state’s water future.

At the same time, many farmers and rural officials have come to agree that some form of regulation is necessary to prevent a tragedy of the commons. The inclusion of local input in the Democrats’ plan was crucial to gaining support from some Republicans outside the legislature. “Last time I checked, there wasn’t Democratic water and Republican water. There’s water for our state,” remarked Prescott Mayor Phil Goode, a conservative Republican who has joined Hobbs in urging the legislature to move forward on the issue. Goode and others stress that water scarcity affects everyone, regardless of party. They view the RGMA concept as a middle-ground approach – more flexible than strict AMA rules, but more proactive than doing nothing. The councils, for example, resemble an idea Republicans themselves proposed earlier (local groundwater boards), indicating some convergence in thought.

Nonetheless, philosophical differences remain. Republican lawmakers like Griffin worry the proposal still represents “executive overreach consolidated in Phoenix,” as Sen. T.J. Shope (R-Coolidge) described it in a prepared statement. They would prefer solutions that require explicit local approval – for instance, allowing counties to opt-in to regulations or to impose modest pumping caps with community buy-in rather than state-mandated targets. During last year’s talks, GOP negotiators pushed for voluntary conservation “caps” that regions could adopt, which Democrats at the time argued would not be sufficient. That unresolved debate over how strict to make the rules is at the heart of why a deal was hard to reach.

described it in a prepared statement. They would prefer solutions that require explicit local approval – for instance, allowing counties to opt-in to regulations or to impose modest pumping caps with community buy-in rather than state-mandated targets. During last year’s talks, GOP negotiators pushed for voluntary conservation “caps” that regions could adopt, which Democrats at the time argued would not be sufficient. That unresolved debate over how strict to make the rules is at the heart of why a deal was hard to reach.

Outlook: Groundwater the Next Water War.

As of mid-March 2025, the Democratic-backed groundwater bills (HB2714 in the House and SB1425 in the Senate) have been introduced but not yet given a committee hearing in the Republican-controlled legislature. GOP committee chairs – including Rep. Griffin herself – have been reviewing the proposal and weighing whether to advance it. Both sides face pressure to address the problem: rural residents and businesses need certainty about water, and there is mounting public outcry to prevent literally “drying up” communities. Governor Hobbs has even hinted she might consider executive action

and SB1425 in the Senate) have been introduced but not yet given a committee hearing in the Republican-controlled legislature. GOP committee chairs – including Rep. Griffin herself – have been reviewing the proposal and weighing whether to advance it. Both sides face pressure to address the problem: rural residents and businesses need certainty about water, and there is mounting public outcry to prevent literally “drying up” communities. Governor Hobbs has even hinted she might consider executive action if lawmakers cannot reach an agreement, though a legislative solution is preferred. Observers say there are signs of possible compromise. Republican leaders assert they “remain committed to working with anyone that shares the goal of protecting rural aquifers and economies,” and Democrats have indicated openness to refining the bill. For example, if the 40% reduction figure is too alarming, the final plan could be adjusted to phase in conservation in a way that farmers can tolerate, paired with incentives or funding to help agriculture transition with less water. There is also discussion of including more recharge projects and data collection (ideas Republicans favor) alongside the regulatory framework. Lawmakers on both sides acknowledge that a balanced solution must both conserve water and sustain agriculture – a true “win-win,” as Griffin put it. In the meantime, each side is making their case to the public. House Republicans, by releasing a detailed analysis and one-page fact sheet critiquing the Democratic plan, are “exposing the radical Left’s agenda

if lawmakers cannot reach an agreement, though a legislative solution is preferred. Observers say there are signs of possible compromise. Republican leaders assert they “remain committed to working with anyone that shares the goal of protecting rural aquifers and economies,” and Democrats have indicated openness to refining the bill. For example, if the 40% reduction figure is too alarming, the final plan could be adjusted to phase in conservation in a way that farmers can tolerate, paired with incentives or funding to help agriculture transition with less water. There is also discussion of including more recharge projects and data collection (ideas Republicans favor) alongside the regulatory framework. Lawmakers on both sides acknowledge that a balanced solution must both conserve water and sustain agriculture – a true “win-win,” as Griffin put it. In the meantime, each side is making their case to the public. House Republicans, by releasing a detailed analysis and one-page fact sheet critiquing the Democratic plan, are “exposing the radical Left’s agenda ,” as Griffin’s press release charged, rallying their base against measures they see as harmful. Democrats, on the other hand, are highlighting stories of rural homeowners whose wells have run dry and farmers worried that without action, there may be no water left for the next generation. They argue that prudent limits now could prevent far more painful consequences later.

,” as Griffin’s press release charged, rallying their base against measures they see as harmful. Democrats, on the other hand, are highlighting stories of rural homeowners whose wells have run dry and farmers worried that without action, there may be no water left for the next generation. They argue that prudent limits now could prevent far more painful consequences later.

Arizonans can expect robust debate on this issue as the legislative session continues. Groundwater has become the latest front in Arizona’s water wars, pitting urgent calls for conservation against fears of government overreach. Despite the clashing rhetoric, there is consensus that the status quo cannot hold – the state’s rural groundwater “lifeline” must be managed in some way to ensure a future for both the people and the economies depending on it. Whether lawmakers can reconcile their differences and craft a bipartisan solution remains to be seen, but the spotlight is on them to strike a balance before Arizona’s water well runs dry.

~~~

Top Image:

Groundwater monitoring at the Coronado National Memorial using a datalogger plugged into a “Leveloader” device for data download. Photo by SonoranDesertNPS. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

at the Coronado National Memorial using a datalogger plugged into a “Leveloader” device for data download. Photo by SonoranDesertNPS. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Leave a Reply