- Groundwater can travel hundreds of kilometers before surfacing in streams.

- Deep groundwater contributes significantly to surface water, especially in the eastern U.S.

- Lateral water flow between watersheds is more extensive than previously estimated.

- Traditional models underestimate inter-basin groundwater flow.

- These findings have major implications for water management and climate resilience.

January 8, 2024 — Groundwater plays a vital role in sustaining streams and ecosystems, especially during dry spells, according to advanced modeling. Recent research published on January 6 on Nature.com reveals surprising details about how far and deep groundwater travels across the continental United States.

reveals surprising details about how far and deep groundwater travels across the continental United States.

Traditionally, water management relied on assumptions that treated smaller watersheds as isolated systems. However, a groundbreaking study led by researchers from Princeton University and the University of Arizona has shown that this perspective is far too narrow. By tracking water particles, the researchers revealed that groundwater flow paths can extend for hundreds of kilometers—far beyond what previous studies suggested.

Deep and Far-Reaching Connections.

The study analyzed data from over 40,000 sub-basins and found that groundwater often originates deep below the surface, traveling through consolidated sediments before discharging into streams. This deep groundwater accounted for over half of the baseflow in 56% of the sub-basins studied, with contributions especially notable in regions with steep topographies, such as the Appalachian ranges and the western U.S.

One striking finding was that groundwater flow paths longer than 50 kilometers (approximately 31.07 miles) are common in areas such as the High Plains and the Gulf Coastal Plain. The longest path recorded spanned 238 kilometers (approximately 147.89 miles), significantly longer than previously observed in smaller-scale studies.

Inter-Basin Flow and Its Implications.

Perhaps the most surprising discovery was the extent of inter-basin groundwater flow. This flow means that many watersheds are not isolated systems but instead exchange water with neighboring basins. Only 0.07% of the watersheds studied were entirely self-contained.

Traditional water-balance models, which estimate groundwater flow based on stream discharge and recharge, fail to capture this dynamic. The researchers found that these models systematically underestimate how much groundwater moves between basins. This has significant implications for water resource management, particularly in regions experiencing water scarcity or contamination.

A Call for Better Models.

The study underscores the need for integrated models that account for both shallow and deep groundwater systems. The research relied on the ParFlow CONUS 2.0 model, a sophisticated tool that simulates 3D groundwater flow across the U.S. Despite its advanced capabilities, the authors acknowledge that no model is perfect. Factors like subsurface structure and recharge rates introduce uncertainties that are difficult to quantify at such a large scale.

Still, the findings highlight the importance of deep groundwater in maintaining streamflow, particularly during dry periods. This underscores the need to protect these hidden water reserves as climate change intensifies droughts and alters water cycles.

The study authors note, “Understanding these connections is critical for managing water resources in a changing climate.” The findings offer a roadmap for improving water management strategies by emphasizing the interconnectedness of groundwater systems.

In the face of increasing water demands and environmental challenges, this research provides a clearer picture of the invisible processes that sustain life on the surface. Protecting groundwater is not just about preserving a resource—it’s about safeguarding the delicate balance of our planet’s water cycle.

Citation.

Yang, C., Condon, L.E. & Maxwell, R.M. Unravelling groundwater–stream connections over the continental United States. Nat Water (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-024-00366-8

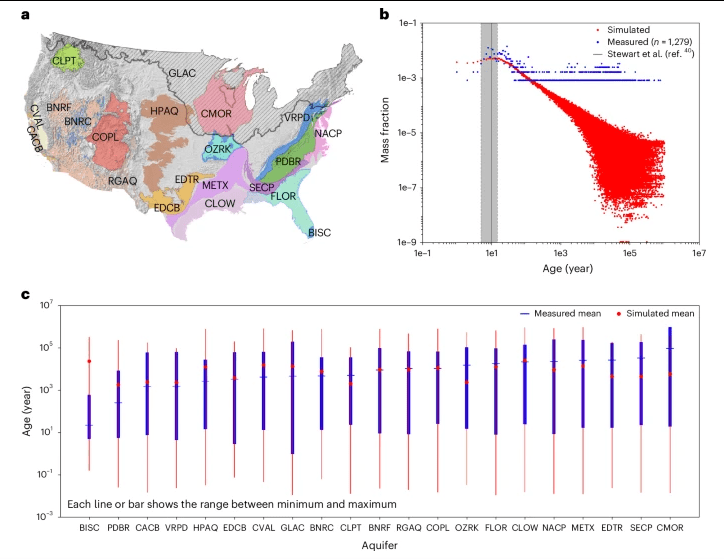

Image from cited report, “Fig. 2: Simulated groundwater ages compare favorably to those reported in literature and expand understanding by providing a more complete age distribution of all aquifers.”